The Garden. Just a place, but is there a more evocative common place name in our language? From the spirit of Eden which pervades our cultural consciousness to today's raised beds in urban areas, the notion of a garden holds a deep charge for many of us, no matter what form it takes.

Gardens can be a few pots of dirt you mess around with and they can be breathtaking, carefully planned and cultivated spaces you can wander and find a place to commune with nature, alone. What about them is so rewarding? It's more than pretty flowers.

The literature of gardening is diverse and voluminous, composed by many experienced and knowledgeable hands, but the first quote that comes to mind is from an amateur. Neil Gaiman, a gleefully inept gardener* and a wonderful writer, remarked, in an essay on how myth is a form of imaginative compost for us humans, "In gardening, the fun is the process; the results are secondary." Whether that process is mucking about in pots, ordering seeds, or planning out the lay of the land with a garden designer, he's right. Of course, it's satisfying and pleasing when the plants come up. The weeding bit can be a bother, but getting our hands in the dirt is good for us, as neuroscientists have recently proven.

Come along with us as we look at the role of the garden in medieval society, examine some principles of good garden design, and praise the virtues of the greenhouse.

The—alas!—late Alan Rickman in front of some wattle fencing in his passion project about the gardens at Versailles, A Little Chaos (2014), which he directed, co-wrote, and starred in.

The Medieval Garden

In the Medieval Ages and into the Renaissance, gardens served several important purposes. At that time, everything in Western Society was ordered according to strict symbolic strictures, trying to parallel and illustrate the scriptures.

The Medieval imagination was almost exclusively informed by the Bible. The Old Testament had two gardens which inspired the gardens of the Middle Ages. While Eden is the more famous, it was the latter, the metaphorical “hortus conclusus”—or “enclosed garden”—of the sensual Song of Songs that had more influence.

Medieval gardens often arranged plantings in squares. Note the wall. Photo by Francois Berraldacci

The enclosed garden, in practice, was a walled garden with various subsections of further wall-like hedges. In text, it was a metaphor for sacred sexuality.

In reality, it served as a space for its metaphorical origin. Enclosed gardens served a basic need, providing privacy within its verdant walls. Such spaces within medieval gardens provided people a place for romantic encounters and intimacy in a society where private space was rare.** This strengthened the connection between gardens and romantic love. In literature from the Middle Ages up to the Modern Era, scenes of romance and the garden as setting for them were seldom far apart.

Medieval garden symbolism is afoot in this tapestry from the Unicorn series, which hangs at The Met Cloisters.

The central garden at The Cloisters is an authentic representation of a medieval garden.

Renowned garden designer Christopher Bradley-Hole writes of them, "The medieval hortus conclusus also provided protection and an opportunity to grow herbs, vegetables, and fruit. Today we feel the same need for the properties that the enclosed garden can give us—shelter from our surroundings and refuge from hectic life outside. The traditional gardens were divided into compartments, usually in a symmetrical arrangement." These carefully planned, artfully arranged gardens also provided a public space for spectacle and entertainment. Music was often commissioned for events held in gardens. To be outside, to slowly promenade through beautiful garden landscapes while music emanated through the air, was a charming highlight of courtly life.

Spring, by Breughel the Younger (1564-1638). A depiction of gardening in the low countries.

Enclosure & Design

Fast-forward to the present day and the notion of enclosure in garden design remains paramount.

Rob Steiner, a garden designer with thirty years’ experience, discusses a garden’s primary role as one of “enclosure.” He argues this is the word’s root meaning. And that this enclosure gives one a sense of security and refuge, as well as allows one to better connect with nature. But there’s a trick of the trade to ensure the appropriate degree of enclosure—it’s no mere abstraction. Steiner says the vertical edge of a space must be at least one-third the length of the horizontal space.

Steiner goes on to emphasize the pivotal importance of a “regulating line,” quoting Le Corbusier: “A regulating line is an assurance against capriciousness…It confers on the work the quality of rhythm… The choice of a regulating line fixes the fundamental geometry of the work.” The appearing wildness of a garden is based on this underlying order. And while it may seem empirical, the exact line chosen is a matter of subjective perception.

Innisfree Gardens, named after a W.B. Yeats poem, in Millbrook, NY

A garden requires some careful planning. Like interior design, it needs layering, contrast, and different textures to stand out and pull a person in.

When planning a garden, one must decide on a few things beforehand. Judy Kameon covers this well in her book, Gardens are for Living. She discusses extending the architectural notion of a “program” to the outdoors. A program asks the question: “What big features do you want to include?” Will there be seating, a pool, a fountain, a firepit? The spatial requirements of these features must be alotted for and become central to the plan. How much “hardscaping” will there be and of what material will it be constituted? Clay, gravel, closely clipped lawn, flagstones? Another consideration is what kind of weather do you have? What soil type? Climate and soil are major factors in choosing what plants to put in.

Letters & Leaves

Questions and ideas like these are commonly encountered in good books on gardening, of which there are many. The library of garden tomes is varied and vast. Throughought the Victorian Era and the twentieth century, there were several noted garden designers with literary ties. To name just two, Russell Page, author of Education of a Gardener, and Vita Sackville-West, gardener extraordinaire, author of several volumes, and friend & lover of Virginia Woolf.

The Garden at The Mount, Edith Wharton's 1902 Lenox, Massachusetts Home

Edith Wharton may have won lasting literary fame for brilliant novels such as The House of Mirth, The Age of Innocence, and Ethan Frome, but she also exemplified and wrote about good interior and garden design. In fact, she co-authored the first book on interior design, The Decoration of Houses, and a volume on the design of gardens, Italian Villas and Their Gardens, illustrated by none other than the singular Maxfield Parrish.

One of Parrish's illustrations for the Italian Villas and gardens Edith Wharton wrote on in their book.

In it, she writes, “in the blending of different elements, the subtle transition from the fixed and formal lines of art to the shifting and irregular lines of nature, and lastly in the essential convenience and livableness of the garden, lies the fundamental secret of the old garden-magic.” She argues in the book that gardens ought to be architectural compositions, just like houses. Another passage—too good not to share—discusses the supporting role flowers and greenery play in Italian gardens:

“The Italian garden does not exist for its flowers; its flowers exist for it: they are a late and infrequent adjunct to its beauties, a parenthetical grace counting only as one more touch in the general effect of enchantment. This is no doubt partly explained by the difficulty of cultivating any but spring flowers in so hot and dry a climate, and the result has been a wonderful development of the more permanent effects to be obtained from the three other factors in garden-composition—marble, water and perennial verdure—and the achievement, by their skillful blending, of a charm independent of the seasons."

But she didn’t just write about garden design, she practiced it. And those wanting to see the results can still walk gardens of her plotting and planning at The Mount, her home in Lenox, Massachusetts. Built in 1902, it remains open as a National Historic Landmark.

Life with a Glasshouse

In high summer, it’s easy to enjoy the heady delights of riotous rows of heather and flower and herb. Smells suffuse the air and the eye drinks in color and contrast, symmetry in the scintillating rays of the sun. Then there's entertaining in the garden—stringing up party lights, gathering near the pool, sitting around a fire under summer stars. While it's a joy to see buds poking their heads out in the spring, the garden is most alive and joyous as a thing of summer.

But a garden offers so much to our lives, is such a source of sustenance, that it’s an excellent idea to have a conservatory or glasshouse on the property. Come the winter months, the life and love of a garden will be there to lighten the short days. Whether an entire separate structure of aluminum and glass or an attached annex to the house, a greenhouse gives you access to working one’s hands in the dirt, to herbs and vegetables and fruits, to sunlight and the special feeling of being surrounded by quiet innocuous living things.

Curved-Eave Even-Span Attached Glasshouse by Under Glass Manufacturing / Lord & Burnham of High Falls, NY

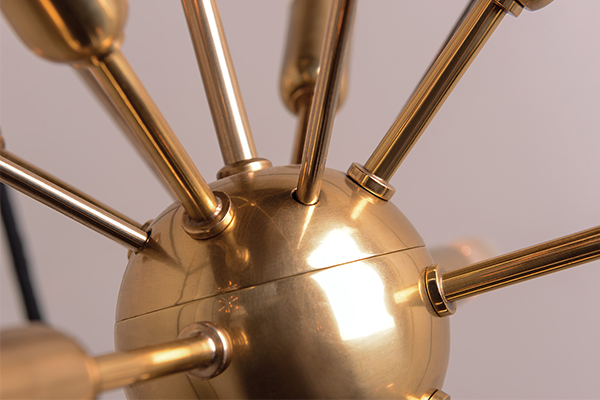

Glasshouse spaces offer a place for some electric lighting. Industrial pendants are a natural fit. It's easy to picture wall sconces such as our Groton, which is UL wet-rated, in a lean-to greenhouse, like the one below:

As it can endure water, an automated sprinkler system or an open door to the elements will do nothing to faze it.

Industrial-style lighting fixtures may also find a place in a certain kind of conservatory, and are ideal sources of task light for a potting room, as seen here in the 2014 House Beautiful San Francisco Designer Showcase House.

Our Pelham pendant illumines a potting station in this room by R.S. McDannell

Thanks for reading.

Head to our Pinterest board, ever-growing, How Does Your Garden Grow, where we collect beautiful, inspiring, and useful pins on the subject.

Have you been to any amazing gardens? Garden yourself and have any tips? Have a favorite garden scene in a movie? We'd love to hear from you in our comments section below!

Featured Image from Period Homes Magazine, a garden by Doyle Herman Design Associates. Click here to read an interview with James Doyle and Kathryn Herman and see more beautiful pictures of gardens they've designed.

*By his own admission. We've not strolled his pumpkin patch in the October Country to see if the claim is true or if it's more of his customary modesty.

**This insight, and much of the Medieval Garden section, was informed by the in-depth scholarly notes to the Orlando Consort's album of medieval garden song, The Rose, the Lily & The Whortleberry, on Harmonia Mundi.