"Six months at sea! Yes, reader, as I live, six months out of sight of land; cruising after the sperm-whale beneath the scorching sun of the Line, and tossed on the billows of the wide-rolling Pacific—the sky above, the sea around, and nothing else!" He's complaining, Herman Melville, in these two lines which launched his literary career. But some of us, like the readers of the 19th century who loved this book and its successor, Omoo, might be envious. What is it like to be out on the ocean that long? To be constantly moving? To have that much fresh air in our lungs? To see such new sights?

Many of us will never know. We'll remain far away from the sea’s crash for too much of the year—“tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks,” as Melville puts it in a more famous book of his. But the allure remains strong. There is something about the infinite, bend to it or buck, intimated in a sea's tangy breath.

Cropping up around the sea, in the cultures of people who lived close to it and the trades of those who worked upon it, came various iconographies and sets of symbols. A visual language. Over time, we loamy landlubbers and homey stuff-lovers have noticed that there’s something just cool about them. Something there is in the systems of a sailboat that is innately pleasing. The way rope is coiled and laid, the variety of knots, the hoisting of sails, the unique lexicon one must use. Anchors, knots, the kinds of clothes best suited for being on a boat. Fashion, always savvy to appropriate signifiers from certain cocultures, has long adapted sailors’ stripes and boathands’ togs. Just look at James Dean and Brigitte Bardot rocking that Breton stripe below:

Coco Chanel launched her nautical line in 1917, where the iconic Breton stripe as a staple in the fashion-sensible lady’s closet was born. The Breton stripe had been the uniform of the French Navy since 1858. Appropriations of nautical gear have been the norm ever since. Looking at some of the things on our Pinterest board for this post, it's easy to see why. In fashion, maritime references make a person seem up for fun and adventure, at the same time they lend a timeless air of class and grace. In home decor, they add an historic charm and dash of whimsy.

What’s amazing is how well just these little hints of the open ocean and the cultural artifacts of life lived on or near the sea can enhance a space. Some people think that to do a whole room with maritime themes would be to go overboard. Or that it would only work in a beach house. And we get that. Those people are correct. (Google nautical decor, if you're feeling brave. A world of horror awaits.) You're walking a fine line with kitsch when you invoke the sea. However, if you add just a touch, it brings in a sense of worldliness. It whispers of the farthest curves of the watery world. It also adds textural intrigue.

Current interior design aesthetics encourage your inner curator to step out. Design blogs and décor magazines lately showcase a lot of spaces where a few different feels work well together. An eighteenth-century French mirror, a Moroccan carpet, a mid-century modern endtable, maybe a Victorian vase, and a reference to the ocean can all be seen pleasantly rubbing shoulders like well-selected guests at a cocktail party, holding each other in perfect poise by virtue of the visual tension their dissimilarities create. It’s a fine-balancing act, not slipping off into chaos, not admitting one thing that would throw it all off. When it's pulled off, the look is excellent, in part because it is not "a look." It's taste. And like the ocean, there is never any end to good taste.

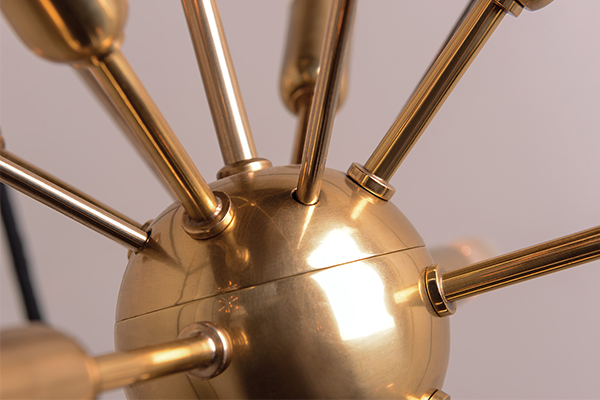

While you won’t find a giant-ball-of-sailor’s-rope table lamp in our collection, we do work a little of that maritime flair in here and there. Our Naugatuck, New Canaan, and Viceroy are all excellent examples.

Our Naugatuck takes inspiration from lighting you would find dockside and on a lighthouse. Using the iconic beehive shape, commonly applied on fox lights (used as deck and cargo lights on ships and now scarce), it fastens on a diffuser of pressed Fresnel glass. While the French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788-1827) did not technically invent the glass that bears his name, he did popularize it by applying it to lighthouses. When used on lighthouses to focus their beacon, these lenses proved most useful, as their concentric circles bend the parallel rays coming from the light source to a common focal length.

New Canaan is done in the traditional style of passageway lights aboard a vessel. Usual 90 degree passageway wall sconces are more plumbing-pipe and straightforward in nature. Our piece adds more visual interest through details such as its conical orb-capped arm, the turning keys connected through to the cage around the light, and the ridged ring in the holder. Not just nautical in appearance, New Canaan is UL wet-rated, making it appropriate for bath and outdoor applications. Take a closer look at its fine details here.

Finally, our new Viceroy makes a lovely pendant for over the captain's table or island light with just a subtle touch of that nautical air. With wire-mesh glass on the diffuser, it was made for rough seas. The detail of the holder, which suggests the arc of an anchor, cements the maritime feeling you get from the piece.

We hope our post on tastefully incorporating nautical decor has put a little wind in your sails. Are you ready to add a maritime touch to one of your rooms? Have you already done a room with an oceanic lean and been thrilled with the results? Let us know in the comments below!