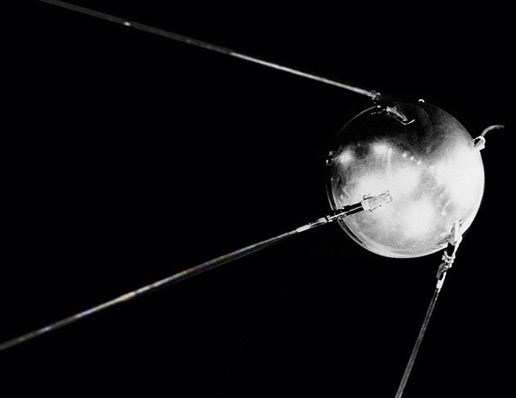

In the opening of his only academic book examining the genre he came to define, Danse Macabre, Stephen King remembers a childhood Saturday afternoon in October of 1957, enjoying a matinee of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. The movie is suddenly interrupted and the lights in the theater come on over an audience of mostly confused and quiet children so that the manager can take the stage and tell them some very important, breaking news.

FIND A SHOWROOM

BUY ONLINE

HAVE AN ACCOUNT?

Hudson Valley Lighting

Troy Lighting

Corbett Lighting

Click the heart icon on an item to start adding favorites!

Email Cart

Email Favorites

Do you have an existing account with us? If so, register here for access to online shopping, pricing, order history and other retailer sales tools.

Interested in becoming a wholesale customer? Please fill out the below contact form and we will be in touch with you shortly!

*By creating an account, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Forgot Your Password?

Attention

Please select a customer from the drop down to order on their behalf. Checking out as “myself” is not an available option.

Attention

Please select a customer from the drop down to order on their behalf. Checking out as “myself” is not an available option.