Leonardo Da Vinci is holding his brush, looking at his canvas, dissatisfied. It looks too artificial, too staged. It all feels so hopelessly wooden.

He's reminded why he listed "painting" so low on that list he made of things he's good at in one of his notebooks. How can he create an accurate depiction of the in-between places in this world? A subtle smile? A gentle gauzy mist rolling up through the hills? The dew rising in the morning?

Exasperated, he looks out the window. In the near-distance, he sees a dome brilliantly reflecting the light cast from the lowering sun's holy fire, giving the house of worship a momentary impression of divine immanence. Yes! THAT! I want to paint THAT! Capture THAT! he thinks (in Italian, of course). He realizes how imprecise and hazy the cityscape is behind the dome, out of focus as the luminescence of the dome's curved surface absorbs his attention. It's not the first time, of course. He's been making observations on this phenomenon for a while, making sketches and notes, practicing perspective and various viewpoints.

An idea seizes him.

He sets up a new canvas and sets some fresh paints on his palette. New forms require new ways! There will be no outlines this time. He'll mix the paint on the canvas. He'll not lay it on thick; he'll proceed with thin, slight coats. The background will be no clear allegorical arrangement, but it will be deliberately of the imagination. It will be a misty wood, a winding waterway, a road vaguely bending. The person sitting in the foreground: her skin will glow, reflecting the day's light in a naturalistic tone. The expression on her mouth, the meaning in her eyes, will be mysterious. Just as a veil seems to separate us from some mystery we cannot completely grasp, a veil will almost imperceptibly cover her hair, marking a boundary between her solid form and the imaginary environment in which she sits.

He dabs the brush and sets at the new canvas quickly with renewed zest, coming at it with oblique and careful strokes, mixing the paints together on the canvas. He places dark colors on the canvas first, like the earthy greens in the background, then applies the thinnest veneer of white atop it. He continues working with painstaking effort, applying gossamer-thin layers.

He's invented many things and he'll invent many more before his days are done. At this moment, he's invented yet another: a new painting technique which will come to be called "sfumato." As far as portrait painting goes, it will change everything: Nothing will ever be the same. Of course, he doesn't know that. He's just pleased to have figured something out and to get closer to his ideals for painting.

This is the little number he's working on:

The word "sfumato" has a few etymologies, but its definition is precise. According to Merriam-Webster, it's "the definition of form in painting without abrupt outline by the blending of one tone into another." One purported etymology is from the Italian for "vanished or evaporated." Another points to fumare for "smoke." Michael J. Gelb in his book How to Think like Leonardo Da Vinci, says, "The word sfumato translates as 'turned to mist' or 'going up in smoke' or simply 'smoked.'"

E. H. Gombrich, in The Story of Art, speaks to the accomplishment of Da Vinci’s sfumato technique: “The blurred outline and mellowed colours…allow one form to merge with another, always leaving something to our imagination…"

Aren't things always better when a little is left to the imagination?

Gombrich continues: "Everyone who has ever tried to draw or scribble a face knows that what we call its expression rests mainly in two features: the corners of the mouth and the corners of the eyes. Now it is precisely these parts which Leonardo has left deliberately indistinct, by letting them merge into a soft shadow. That is why we are never quite certain in what mood Mona Lisa is really looking at us."

This idea was too good to simply keep to the world of painting.

Just as ideas from the fashion world find their way into interior design today, the art world informed other crafts in the Renaissance. And with Florence so close to Venice, it was natural that the revolutionary artists of the former would influence the master glassmakers of the latter.

Looking to find new ways to add texture, depth, and mystery to their craft, these glassmakers adapted the idea of sfumato.

How?

By blowing smoke into glass as they formed it.

The results are rare. It's a new approximation of this seldom-seen sfumato technique you see in Hudson Valley Lighting's new family, Sawyer.

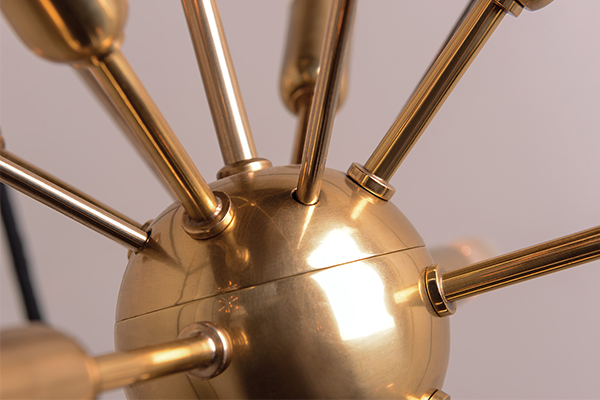

For those desiring a little more mystery, a little more room for the imagination to drift and wander in the domestic sphere, Sawyer delivers. Its thick round diffuser partially conceals a contemporary metal candelabra with tubular bulbs. The glass is created using a special technique, not blowing smoke into the glass as glassmakers centuries past did it, but in a new way which, in keeping with our theme, will remain a mystery at this time. With the ambience of a master illusionist's show, the thick glass diffuser appears to be filled with dissipating vapor, a mysterious mist. The result is a pendant suspended from a hang-straight canopy which achieves a rich sense of atmosphere.

Photograph by Alyssa Rosenheck. From our 2017 Catalog. Please do not distribute.